EO Opera Editions

The challenges inherent in producing a useful and historically valid performing edition of a baroque opera are many and varied.

In baroque times, operas were created around casts, rather than casts being formed for operas, and works were scarcely ever revived without significant alteration. Even during a run of performances an opera was routinely amended in response to feedback from singers or to reflect the reaction of the public. Thus, a manuscript of a baroque opera score is a somewhat provisional assembly of dozens of component parts, some of which might be omitted, some of which are optional additions, and some of which are alternatives to each other. New editions can all too easily get bogged down in trying to demonstrate the full evolution and vicissitudes of the score.

A purist musicological approach might attempt to delineate all the complex multi-layers. Certainly, by segregating a main score from various appendices of alternative layers it is possible to create a resource that enables the user to reconstruct the opera in multiple forms: the form it took on its first night, or the form it took at the end of its initial run, or the form it took in a subsequent evolution.

The main performing text could be presented as ‘standard’ and the appendices as ‘legitimate deviation’, with no further attempt to influence the user in selecting options for addition or suppression.

For some scholars and musicians, the ideal towards which a modern performance should strive is authenticity, or an aural facsimile of a chosen historical performance - often the first performance of the work, but sometimes its final or ‘ideal’ form. Such ‘authenticity aficionados’ fiercely object to the practice of eclectic selection of elements or the conflation of different historical units, on principle. But arguably such a constrained approach diverges from that of the baroque masters themselves. Theirs tended to be a somewhat confused world of hasty adaptations, day-to-day collaborations, and cross-borrowings (sometimes overt imitatation, emulation, or paying homage to colleagues). Not only did they accept new or substitute ‘import’ arias at the drop of a hat, but also decoration and improvisation were the natural tools of their trade.

Our approach.

In working on our editions, we try to balance a judicious, practical approach with respect for historical veracity. Baroque impresarios and composers were pragmatists and we follow in their footsteps. For them, the optimum version of an opera was the one that pleased the public best. Given the choice of three different versions of a given aria the one chosen was the one most likely to please: strongest musically, dramatically most apposite, best suited to the singer, and so on.

In modern times, just as in the period of the baroque, arguably the most important objective is the creation of a cohesive musical piece in which the progression of the different elements, and indeed the features of each component, make sense both musically and dramatically. This is a core aim for us - to give the work new life for the 21st century. However, as we undertake the different aspects of our adaptation, our overarching principle is to remain as close as possible to the original spirit and intention of the composer.

We aim to produce multi-purpose and functional editions which also offer a sample realization of the continuo, recognising that this might be ignored by the specialist professional but might be invaluable to the less experienced.

The text.

In handling the literary text, we strive for a balance between accuracy and accessibility not only in the positioning of the words as they underlay the notes in the score, but also in the translation or choice of wording for our sur-titles. There is surely a powerful argument for realism and contextual veracity in deciphering language since it is an intrinsic part of the whole piece; just as musical modifications are judicious, so too are adjustments to the text. We do not favour the practice of 'updating' the text with modern colloquialisms or rendering it into poetic rhyming vernacular to please the eye or ear of a contemporary English audience.

It is worth noting that the words on the score in retrieved manuscripts do not always match the text in the libretto. Libretto text and the text on the score often underwent a separate evolution, as the poet continued to polish his verse and the composer sometimes introduced changes, either consciously or accidentally. Some changes – for example, repetitions of isolated words and phrases within a recitative, or repetitions of words within arias – were made for valid musical or musico-rhetorical reasons. Others arose by accident when lines were misread or errors in the text remained uncorrected.

For this reason, the text surviving in the extant libretto is not viewed as the primary source but the secondary: though it is consulted it does not override on principle the readings derived from the score.

For singers, the ancient Italian often requires some degree of modernisation so that the text makes sense and can be sung musically (words matching notes). It is preferable not to alter the phonetic quality of a word or the syllabic scan of a line.

As regards surtitles, again the ancient Italian presents problems since some words are now obsolete. Also, to make the language and context comprehensible to modern audiences, some of the literary references benefit from demystification by the judicious addition of brief 'definitions'. For example, in a recent edition of Cavalli’s L'Egisto the cast were offered guidance in getting to grips with their characterisation, and the audience were occasionally given additional 'support' within the sur-titles (e.g., as to the nature of the named river ('of wailing').

“17th-century thinking still included the perception that the stars and the planets had control over the ‘baser’ elements of human nature. On stage at least, audiences expected to see gods interfering in the lives of humans. They could not only identify with, but also visualise, life-journeys where characters trod the treacherous tightrope between fiery damnation in the underworld and attaining the glorious delights of a heaven behind gem-encrusted gates, and where ‘fate’ had the upper hand.

It is easier to grasp the essence of what the characters are saying if we can understand some of the mythological or supernatural reference points that would have been well-known to a 17th-century audience. Thus, it helps to know that: Avernus was the entrance to the underworld; there were five rivers in the underworld, including the Styx which was the river of shuddering, or loathing of death; the Phlegethon which was the flaming river; the Cocytus which was the river of wailing; and the Acheron which was the river of woe; Elysium or the Elysian fields is paradise; the gardens of the Hesperides belonged to the goddess Hera included a grove of apple trees that yielded golden apples; Apollo is the god of the sun (his byname is Phoebus); Egisto is the son of Apollo; Jupiter (Zeus) is the god of the sky and is king of the gods; Pluto (brother of Jupiter) rules the underworld; Venus is the goddess of love; Cupid is her offspring; Flora is the goddess of flowering plants; Vulcan is the god of fire; Eunomia was the goddess of law; the Hours (Horae) were goddesses of the hours of the day / months / seasons of the year; and the Scythians were ancient warriors who lived in Siberia.

If we can become a little more at ease with the concepts that 17th-century audiences took for granted, then we can better understand character motivation, what engendered fear, the nature of anger, the rationale behind jealousy, and the bizarrely changeable nature of Love.”

Musical Scores available.

-

Céphale et Procris

ELISABETH-CLAUDE JACQUET DE LA GUERRE

-

Musiche Sacre

CAVALLI

-

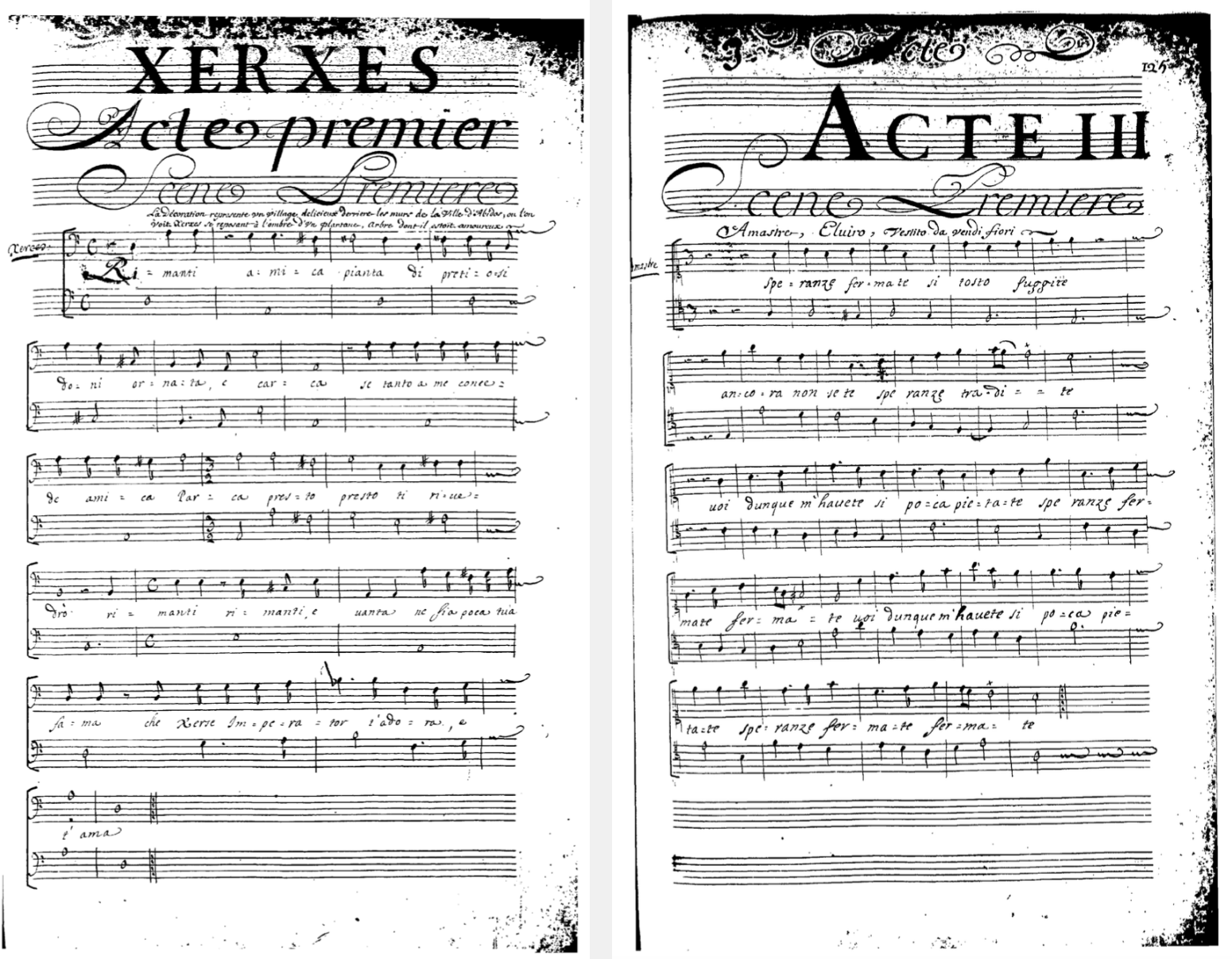

Xerse

CAVALLI

-

L'Egisto

CAVALLI

-

L'Euridice

CACCINI

-

Petite Pastorale

CHARPENTIER

-

Il faut rire et chanter

CHARPENTIER