Les Indes Galantes 2022

4 - 12 FEB 2022, 7:30PM

Les Indes Galantes

RAMEAU

4th, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, 12th February 2022 7:30pm

The Cockpit Theatre, Gateforth Street, London

Ensemble OrQuesta Baroque

Marcio da Silva Music/Stage Director

Laura Hensley Assistant Stage Director

Petra Hajduchova Harpsichord

Cédric Meyer Archlute

Kirsty Main, Eloise MacDonald Violin

Alexis Bennett Viola

Erlend Vestby Cello

Joel Raymond Oboe/Recorder

Angela Hicks Hébé

Poppy Shotts L'Amour

Flavio Lauria Bellone

Helen May Emilie

Kieran White Valère

Jack Lawrence-Jones Osman

Angela Hicks Phani

Samuel Jenkins Don Carlos

Jack Lawrence-Jones Huascar

Anna-Luise Wagner Fatime

Poppy Shotts Zaïre

Kieran White Tacmas

John Holland-Avery Ali

Les Indes Galantes.

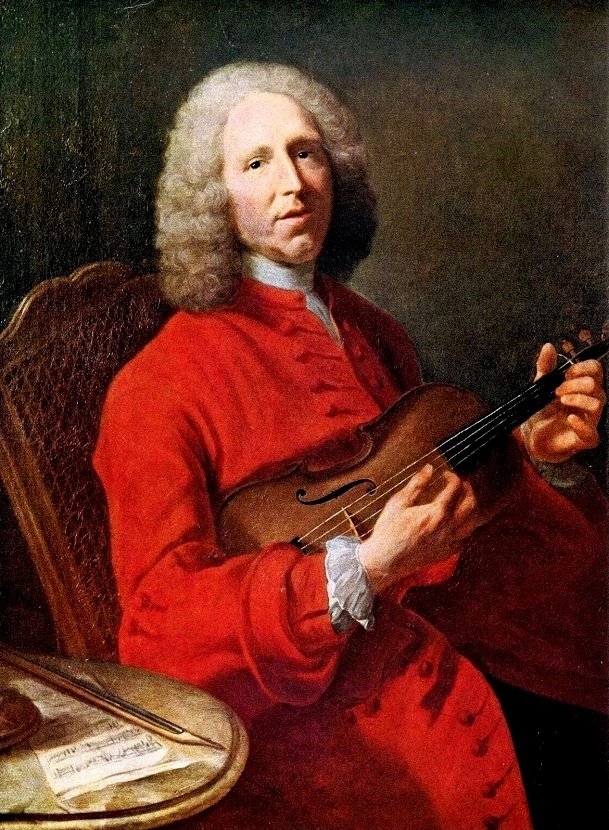

Les Indes Galantes, ('The Amorous Indies’), composed by Jean-Phillipe Rameau (1683-1764), was premiered by the Académie Royale de Musique at the Théâtre du Palais-Royal in Paris on 23rd August 1735. It was a hybrid work written for public entertainment and was performed more than 60 times in its first two years.

Rameau was one of the most important French composers and music theorists of the 18th century, but he was almost 50 before he wrote the first opera (Hippolyte and Aricie, 1733) of the 31 on which much of his lasting reputation now rests. Les Indes Galantes was his second performed opera. The integration of instrumental, vocal and dance elements into a single evening’s performance, with an exotic setting, sumptuous costumes, and elaborate scenery, was very popular during the Baroque period. Rather than offering a single story in several acts, Rameau and his librettist, Louis Fuzelier (1672–1752), opted for a sequence of tales set in far-flung places (the ‘Indes’ of the title represented any remote and little-known place which was therefore considered to be exotic).

For its original performance there were only three parts: a prologue and two acts (or ‘entrées’, as Rameau called them). The premiere met with a lukewarm reception from the audience, and, at the third performance, a new entrée was added under the title Les Fleurs. It is this early formulation of a prologue and three acts, that is used for our current production. In the event this additional entrée caused further discontent because it showed the hero disguised as a woman, which was viewed by some as an absurdity and by others as an indecency. Thanks to the forbearance of his immensely wealthy new-found patron Alexandre Le Riche de La Poupelinière, Rameau was able to make a series of further revisions. This makes the task of reassembling the score extremely difficult.

Subsequently the entrée des Fleurs was replaced with some new music, and later on a fourth entrée - Les Sauvages - was appended; this entrée is not included in our production.

Director’s note.

MARCIO DA SILVA

In this production our company become a ‘troupe’ of artists in a non-specific world, briefly bringing ten distinctive characters to life. I have focused on the core messages behind each element of the libretto.

Prologue: a path on the floor signifies the journey ahead – different places, different characters, different stories - and our own path through life. Love and Hébé invite three pairs of lovers to fire their flame and live their passions. They comment on the endlessly repetitive cycle of relationships. Bellone (somewhat flippantly) invites them to glory - their response, though sometimes enthusiastic, lacks sustained commitment: despite Bellone’s best efforts, our lovers are perhaps too easily distracted.

The zigzag movement represents the way that we unwittingly fall into cycles of repeated behaviour and how our lives sometimes follow patterns. This is also reflected in the static choreography performed by the lovers; they repeatedly go through different stages of a relationship, portraying a pattern or cycle. In the duet and chorus ‘Traverser’, the troupe follow the light and fly into other unknown places to tell their stories.

Entrées - Each story is told in or around a box containing experiences, memories, and feelings; characters alternate through the corners of the box to acknowledge different perspectives of the same story.

Turc – the heart of this story focuses Osman’s renouncing of his love in favour of Valère and Émilie’s happiness. Émilie’s anguish and Rameau’s storm coincide in a powerful moment of non-linear dramatic action.

Les Incas – this story reminds us that one person’s hero is sometimes another’s villain. Phani, criticizes the use of religion as a persuasive tool, yet believes in the superpowers of the Spanish who arrive in big ships. Huascar, whilst admittedly vile in his own attempt to persuade Phani to marry him, is arguably justified in criticising the Catholic Spanish for worshipping Gold above God. Huascar’s prophetic words: ‘each day can be your last’, tragically predicts his fate, as well as the fate of his civilisation.

Les Fleurs – amidst the comic elements and cross-dressing, the core message, exemplified in the glorious final quartet, is of love and destiny: those who are meant to be together will end up together.

Synopsis.

Prologue - Hébé, goddess of youth, summons her followers to take part in a festival. Young French, Spanish, Italians, and Poles rush to celebrate. The celebration is interrupted by the noise of drums and trumpets. It is Bellone, goddess of war, who arrives on the stage accompanied by warriors bearing flags. Bellone calls on the youths to seek out military glory. Hébé prays to L'Amour (Cupid) to use his power to hold them back. L'Amour arrives and decides to abandon Europe in favour of the ‘Indies’, where love is more welcome.

The first act - ‘Le Turc généreux’ - is set on an island in the Indian Ocean. Osman Pasha is in love with his slave - a French girl Émilie whom he has taken captive, but she rejects him, telling him she was about to be married when a group of brigands abducted her. Osman urges her to give up hope that her fiancé is still alive but Émilie refuses to believe this is true. The sky turns dark as a storm develops, (providing the musical focal point of this section). Émilie sees the violent weather as an image of her despair. A chorus of shipwrecked sailors is heard. Émilie laments that they too will be taken captive.

Émilie recognises one of the sailors as her fiancé Valère. Their joy at their reunion is tempered by sadness at the thought they are both slaves now. Osman enters and is furious to see the couple embracing. However, unexpectedly, he announces he will free them. He has recognised Valère, who was once Osman’s master but magnanimously freed him. Osman gives Valère gifts and the couple praise his generosity. They call on the winds to blow them back to France. The act ends with celebrations as Valère and Émilie prepare to set sail.

The second act - ‘Les Incas du Pérou’ - is set during a Festival of the Sun in Peru, and also concerns a love triangle: a Spaniard, an Incan princess, and an Incan high priest. Don Carlos, a Spanish officer, is in love with the Inca princess Phani. He urges her to escape with him, but she fears the anger of the Incas, who are preparing to celebrate the Festival of the Sun. Nevertheless, she is prepared to marry him. The Inca priest Huascar is also in love with Phani but suspects he has a rival and decides to resort to subterfuge. Huascar leads the ceremony of the adoration of the Sun, which is interrupted by a sudden earthquake. Huascar declares that this means the gods want Phani to choose him as her husband.

Don Carlos enters and tells Phani the earthquake was a trick, artificially created by Huascar. Carlos and Phani sing of their love, while Huascar swears revenge. Huascar provokes an eruption of the volcano and is crushed by its burning rocks. Musically Rameau’s dramatic skill is displayed in his portrayal of the destructive force of Huascar’s jealousy (mirroring the fire and rocks hurled from the volcano, and the unleashing of the menacing force of the earthquake).

The third act - ‘Les Fleurs-fête Persane’ - is set in Persia and concerns suspected infidelity. There is intended humour here with disguises, mistaken identities and a concluding fete celebrating a happy outcome of preceding events. Both the text and music have a light-hearted spirit.

The interactions are complex. Prince Tacmas is in love with Zaïre, a slave belonging to his favourite Ali, even though he has a slave girl of his own, Fatime. Tacmas appears at Ali's palace disguised as a merchant woman so he can slip into the harem unnoticed and test Zaïre's feelings for him. Zaïre enters and laments that she is unhappily in love. Tacmas overhears her and is determined to find out the name of his rival.

Tensions mount when Fatime enters, disguised as a Polish slave, and Tacmas believes he has found Zaïre's secret lover. Enraged, he casts off his disguise and is about to stab Fatime when she too reveals her true identity. It turns out that Zaïre has been in love with Tacmas all along just as Fatime has been in love with Ali. We hear a beautiful quartet ('Tendre amour, que pour nous ta chaine dure a jamais’) – a rarity for Rameau – as the two couples rejoice in this happy resolution. There is a heady chorus to end, as the Persians celebrate the Festival of Flowers.

Response to Rameau’s music.

In France Rameau’s operas are performed often, both at the Paris National Opera and in many of the regional opera houses. He is hailed as one of the country’s greatest composers, and his music is promoted and performed with pride by many of its finest musicians, notably Les Arts Florissants. By contrast, England focuses much more on Handel and Monteverdi, and Rameau’s operas are aired much less frequently.

However, musically Rameau offers great riches. He was undoubtedly a revolutionary; his use of harmony and orchestration was way ahead of its time, and his understanding of the harmonic and sonic possibilities of the orchestra is astounding. Indeed, some see Rameau as one of the first impressionists, exploring textures and sonorous string sounds that would lead to Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande and inspire Camille Saint-Saëns to edit his works. Berlioz and D'Indy revered him.

There is no doubt that Rameau’s music provoked controversy. His first opera, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), caused a stir among the Parisian intelligentsia, dividing opinion between conservatives who declared Rameau's music to be difficult and the work of a theorist, and those who embraced his innovations. Among his advocates, André Campra, one of the leading composers of his time, declared: "There is enough music in this opera to make 10 of them; this man will eclipse us all." When Les Indes Galantes was first performed, Rameau was again reproached for the extreme difficulty of his music.

Many of Rameau's advances came from adopting the fashionable Italian techniques of his day, such as using the full orchestra to accompany sections of recitative. But Rameau took these innovations to new heights, and underpinning his music is a specifically French sensibility. The French were said to speak their operas and sing their plays; in Rameau's day, some of the principal singers in his operas would have been thought of as actors as much as singers. In contrast to the Italian composers, the French would not have used castrati and had little time for divas: opera was more egalitarian, with the music shared more equally between soloists, chorus, and orchestra. In Les Indes Galantes - and in Castor and Pollux (1737) - you can already sense this social revolution taking shape. But perhaps most French of all is the way in which Rameau weaves dance and movement into the fabric of his work: more than mere divertissements, they elucidate character and plot.

Modern audiences.

Rameau’s defenders have suggested that the opera is not in fact just a dose of French gallantry conquering all. Our audience might be persuaded that the opera can sustain an alternative interpretation. Arguably the core motif holding the acts together is the trope of the ‘noble savage’. This presents indigenous populations, especially people of colour, as holding some innate virtue due to their lack of contact with ‘civilisation’. A close observer might propose that the narrative ultimately portrays Turks, Persians, Peruvian Incas, and American natives to be more virtuous than the cynical, greedy, and sometimes rather cruel Europeans. In fact, Rameau's 'natives' seem to be giving the ‘civilised’ an example of noble feelings, fearlessness, and generosity.

But the stereotyping within this alternative assessment is clearly still problematic, giving us further food for thought. There is no doubt that these two core issues of the long shadow of colonialism and the dangers of latent racial stereotyping raised by Les Indes Galantes are alarmingly current. As we debate over the statutes of slave traders, disagree over the handling of refugees, and clash over our response to #BlackLivesMatter, perhaps this opera can challenge us to ask whether we have really laid to rest the destructive ghosts of colonialisation. Since our daily news is still haunted by inappropriate and clumsy use of racial stereotypes, perhaps we are not as far removed from Rameau’s world as we would like to believe.

So where does this leave us? Our artistic task is to find ways to encourage 21st century audiences to view Les Indes Galantes through a fresh lens and to find joy and meaning therein. Some modern productions – such as Platée at the Royal Opera House – opt for the historically accurate approach, with elaborate costumes, extravagantly plumed headdresses, and ornate sets. This is only one view of how Rameau might be performed. Arguably, if we simply try to recreate the past, we turn what surely should be living theatre into a historical curiosity.

That said, it is not our intention to re-invent, re-imagine, or re-interpret simply for the sake of inconsequential impact, but to bring Rameau’s creation to life in a dynamic and collaborative way with our artists and in an insightful and meaningful way for our audience. In essence we offer the music and the drama stripped down but vibrant. In baroque times dance was a key element of opera performances, and some modern performances of baroque operas retain dance episodes. By contrast we offer a distinctive stylised approach. Simple choreographic gestures are incorporated within the drama, and our singers often move on stage in patterns in a manner that not only recognises the connection between movement and music but also exemplifies character interactions. We hope our minimalist approach leaves the audience free to hear the beauty of the music and enables individuals to develop their own nuanced interpretation.

There is perhaps a final question to be asked as to whether the opera has anything relevant to say to its audience about human nature and relationships. Despite the ‘exotic’, and therefore slightly ‘removed’, locations, Rameau certainly intended that his audience should see themselves reflected in the human characters and emotional issues that he portrayed: the sultan who declines to take advantage of the highly desirable prisoner; the self-destructively jealous Inca priest; the love games of Persian princes; and the prairie Indians who love faithfully and peacefully. Equally his intention that the furiously portrayed storms and volcanic eruptions should represent their emotional turbulence also has a resonance. On a fundamental level, perhaps human nature and the trials and tribulations of falling in and out of love retain recognisable common denominators, whether the backdrop is the exotic 18th or the everyday 21st century.

Rameau comes under heavy criticism for Les Indes Galantes. Even though the multiple plots take place in a fantasised exotic ‘elsewhere’, the portrayals of distant lands are seen by critics as a representation of primitive clichés. The apparent pervading impression of Enlightenment superiority all too easily comes across as propaganda for colonialism. Furthermore, just in case you are whimsically inclined to see 'love across social divides' as an amiable message within the different plot-lines, the libretto is intensely problematic, being full of rather offensive moments. For example, when two Persian men fall in love with each other’s female slave, one of the masters openly declares, ‘Love is necessary in slavery. It sweetens the hardship.’

How do we handle such a reductive world view – do we redact it, or simply avoid it.

Is Rameau’s 18th century world view too far removed from ours to have any relevance and do the themes that he explores have any current applicability.

Reluctant though one might be to quote right wing US politicians, Allen West made a valid point when he said: ‘History isn’t there for you to like or dislike. It’s there for you to learn from it. If it offends you, that’s even better, because then you’re less likely to repeat it. It’s not yours to erase or destroy’.

I for one am reluctant to discount such a musical masterpiece on the grounds that Rameau’s 18th century perspective is too disconnected from ours to be of interest. His music is rich and powerful, and the theme of colliding cultures that he explores does have modern-day applicability. The opera can challenge us to consider issues of identity and alterity in current society. After all, for all our liberal talk of the beneficial inter-connectivity brought about by increased globalisation and the enhanced awareness of equality generated by multiculturalism, it is evident that today’s world is fundamentally fragmented by long-standing racism and shaken to its core by a xenophobic backlash against the challenging ramifications of a refugee crisis of unparalleled proportions.